Crisis Response

Crisis Response programs are made up of teams of individuals trained to intervene in cases where youth’s health or safety is threatened, resolve serious conflicts between parent/guardians and the youth regarding the youth’s conduct or disregard for authority, or runaway behavior. Law enforcement notifies Crisis Response teams when they are called to a location where there is a situation as mentioned above, and the staff/team works with the youth and their family/those involved in the situation to come to a solution the make sure the youth and others are safe. The solution can include creating a safety plan with the youth and family, services being provided to the youth and family to keep the youth at home, and/or the youth being places outside of the home. The Crisis Response staff/team can also recommend services within the community to address the needs of the youth/family as part of the resolution process, and follow-up with the family if needed.

Crisis Respite falls under Crisis Response programs, and is a temporary placement for a youth outside of the home to provide relief for parents or caregivers. This is not an extended placement.

evaluating crisis respite programs

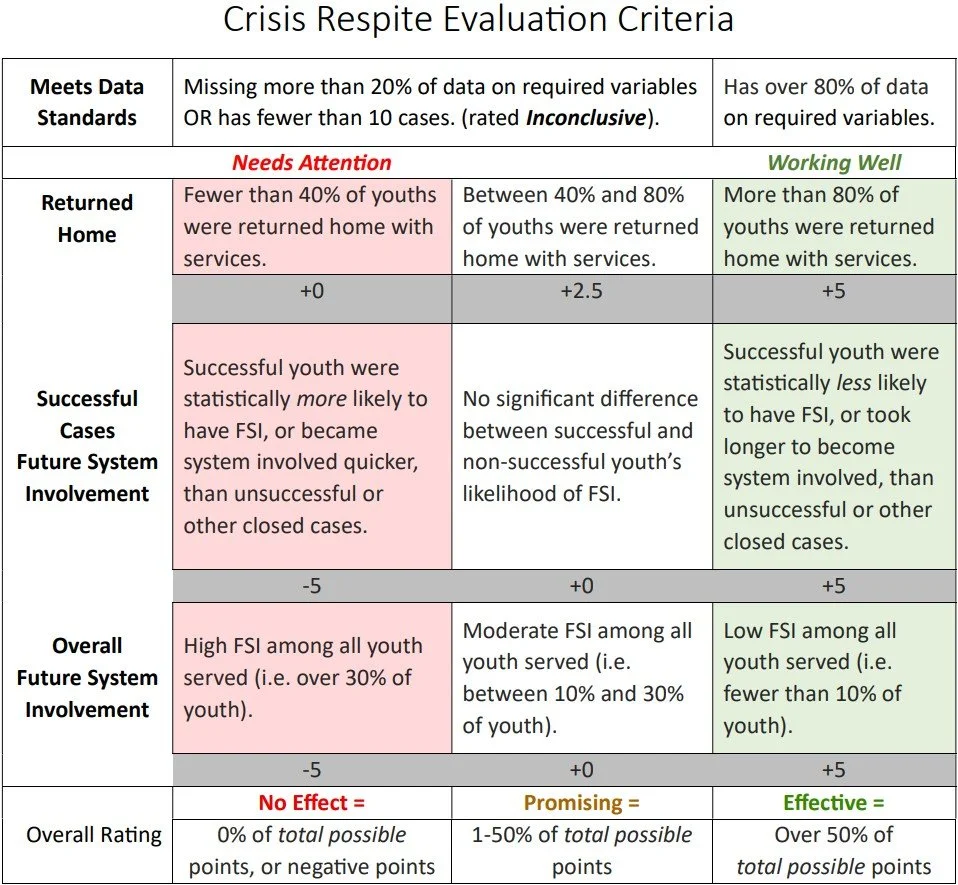

As part of our yearly evaluations for Community-based Juvenile Services Aid funded programs in fiscal year 2025, the JJI, in partnership with the NCC, developed evaluation matrices to categorize important outcomes for each program type evaluated. The following categories describe the important program outcome indicators for crisis respite programs. These categories can be used to assess the standing of a program in terms of whether it is successfully applying best practices and meeting expectations or common goals for such programs.

Evaluation Framework

Any program assessment must start by reviewing what data is available on processes and outcomes. Incomplete data or small sample sizes (i.e. few client cases) increase the risk of error in analysis. Shreffler and Huecker (2023) describe what Type I and II errors are – with high risks for error we might fail to identify a positive impact that’s occurring or falsely state the program was effective when it wasn’t. Small sample sizes run the risk of an outlier (one or two cases with unique, or very low/high values in an outcome) skewing the results.

A major goal of the Community-based Juvenile Services Aid (CBA) and Juveniles Services Commission Grant (JS) funding is to provide community-based services for juveniles who come in contact with the juvenile justice system and prevent youth from moving deeper into the system. CBA/JS funded programs are evaluated on how effective they are at preventing future system involvement (FSI) after youth are discharged from the program. FSI is evaluated in two ways – 1) comparing FSI between successful cases and unsuccessful cases and 2) overall FSI for all youth served. Evaluating these metrics gives a program the overall picture of FSI for the youth they come into contact with and helps programs more deeply understand how successful completion or discharge from their program impacts FSI of youth.

The following is a brief review of some of the existing literature related to crisis response programs to further explain the importance of evaluating these outcomes in rating program effectiveness. Please note: There is an overall lack of peer-reviewed research on crisis respite programs, so the following review focuses on crisis intervention research and best practices.

Brief Literature Review

Crisis response services play an essential role in diverting youth (especially youth with serious emotional or behavioral challenges) away from system involvement, as these programs aim to provide immediate intervention and connect youth with services during crisis events rather than applying the traditional justice system response of arrest or detainment.

Effectiveness

A recent review compared the effectiveness of crisis intervention teams (police trained in mental health and de-escalation techniques), co-responder models (police paired with a trained mental health professional), and non-police models. They found co-responder models often led to increased referrals and service linkage, whereas police-only programs tend to default to arrest or transport to treatment (Marcus & Stergiopoulos, 2022). While research evaluating crisis response models specifically designed for youth is scarce, one Florida juvenile co-responder program was shown to lead to lower involuntary commitments and higher rates of de-escalation, allowing youth to stay in their community (Childs et al., 2024).

Best Practices

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recently published a report to outline core principles and strategies crisis response programs can follow to effectively address youth crises (see full report below; SAMHSA, 2022). They note that youth crisis systems should form a continuum of care that include three core components:

Someone to talk to (crisis call centers)

Someone to respond (mobile response teams)

A safe place to be (stabilization services)

They also encourage crisis programs to:

Keep youth in their homes as much as possible

Provide developmentally appropriate services that treat youth as youth

Integrate family and peer support providers in service planning, implementation, and evaluation

Provide culturally and linguistically appropriate services

For additional resources or to access articles referenced above, contact the JJI at unojji@unomaha.edu.

additional resources

The National Alliance on Mental Illness website has information and best practices for Crisis Intervention, including in youth.

The Vera Institute published a brief describing how respite care can be applied to youth status offenders to prevent court-ordered placements or detention. apt solution for youth status offenders.

Additional Research

A Meta-Analysis of 36 Crisis Intervention Studies (Roberts, A. & Everly, Jr., G 2006)

This article is designed to increase our knowledge base about effective and contraindicated types of crisis intervention. A number of crisis intervention studies focus on the extent to which psychiatric morbidity (e.g., depressive disorders, suicide ideation, and posttraumatic stress disorder) was reduced as a result of individual or group crisis interventions or multicomponent critical incident stress management (CISM). In addition, family preservation, also known as in-home intensive crisis intervention, focused on the extent to which out-of-home placement of abused children was reduced at follow-up. There are a small number of evidence-based crisis intervention programs with documented effectiveness. This exploratory meta-analysis of the crisis intervention research literature assessed the results of the most commonly used crisis intervention treatment modalities. This exploratory meta-analysis documented high average effect sizes that demonstrated that both adults in acute crisis or with trauma symptoms and abusive families in acute crisis can be helped with intensive crisis intervention and multicomponent CISM in a large number of cases. We conclude that intensive home-based crisis intervention with families as well as multicomponent CISM are effective interventions. Crisis intervention is not a panacea, and booster sessions are often necessary several months to 1 year after completion of the initial intensive crisis intervention program. Good diagnostic criteria are necessary in using this modality because not all situations are appropriate for it. PDF

Is Solution-Focused Brief Therapy Evidence-Based ?(Kim, Smock, Trepper, McCollum, & Franklin, 2010)

This article describes the process of having solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) be evaluated by various federal registries as an evidence-based practice (EBP) intervention. The authors submitted SFBT for evaluation for inclusion on three national EBP registry lists in the United States: the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), What Works Clearinghouse (WWC), and Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). Results of our submission found SFBT was not reviewed by SAMHSA and WWC because it was not prioritized highly enough for review, but it was rated as “promising” by OJJDP. Implications for practitioners and recommendations regarding the status of SFBT as an EBP model are discussed. PDF

Randomized trial on the effectiveness of long and short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy and solution-focused therapy on psychiatric symptoms during 3-year follow-up (P. Knekt, et al 2007)

Background. Insufficient evidence exists for a viable choice between long- and short-term psychotherapies in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. The present trial compares the effectiveness of one long-term therapy and two short term therapies in the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders.

Method. In the Helsinki Psychotherapy Study, 326 out-patients with mood (84.7%) or anxiety disorder (43.6%) were randomly assigned to three treatment groups (long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy, short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy, and solution-focused therapy) and were followed up for 3 years from start of treatment. Primary outcome measures were depressive symptoms measured by self-report Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and observer rated Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD), and anxiety symptoms measured by self-report Symptom Check List Anxiety Scale (SCL-90-Anx) and observer-rated Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA). Results. A statistically significant reduction of symptoms was noted for BDI (51 %), HAMD (36 %), SCL-90-Anx (41%) and HAMA (38%) during the 3-year follow-up. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy was more effective than long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy during the first year, showing 15–27% lower scores for the four outcome measures. During the second year of follow-up no significant differences were found between the short-term and long-term therapies, and after 3 years of follow-up long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy was more effective with 14–37% lower scores for the outcome variables. No statistically significant differences were found in the effectiveness of the short-term therapies. Conclusions. Short-term therapies produce benefits more quickly than long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy but in the long run long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy is superior to short-term therapies. However, more research is needed to determine which patients should be given long-term psychotherapy for the treatment of mood or anxiety disorders. PDF